-

February 28

The picture is from yesterday, when it was sunny and untimely warm and the body enjoyed spring, although the mind understood how strange and bad it is to have spring in February. Today is humid, gloomy and very warm, 16 degrees above the average for the season, and the wind is howling something frightening. We’re expecting a flash freeze tonight and are almost placid about the possibility that we will lose electricity. Or maybe we won’t, in which case we will consider ourselves lucky.

These days, I have received several invitations from people I respect and for the opportunities that could open other doors. Usually, I would be torn between my inability to say no (I really do feel like I owe every person who asks me something) and my ambition that would push me to say yes to everything. Today, I was able to say “no, thank you, it sounds wonderful, but it is not right for me” and actually mean it. It is alarming that I do not remember another time I’d put my well-being above my ambition. I hope this is a start. So, let me write it down and repeat it:

not everything is for me

not every time is right

it’s ok to say no

saying no may empower other people to say no

there is more than one way to love people and more than one way to make a change

-

February 26

The little one is sick today, not enough to unsettle me, but just enough to stay at home and turn what was supposed a busy working day into a smooth drifting between cuddles, answering emails, playing and fitting some deadlines in between. It was such an unbelievably quiet day. A day that feels incredibly full and satisfying although objectively nothing happened. A day when we lived every minute without rushing through it. Thank you, my little troublemaker, for teaching me to slow down.

-

February 25

The weekend has been mercifully sunny. It still surprises me, although it shouldn’t, how much power they, the sun, the moon, the winds have on us. It still surprises me, how much time there is and how much one does when one has “nothing to do.” I start seeing the weekend as reconnection to kairos, full and expansive, uncensored. A time when one can grieve or rejoice without toning down or sweetening up. I’ve done both. I even spent a whole hour sitting on a couch and reading for pleasure and still had time in the evening to prepare for my Mohawk test and write an outline for an intercultural leadership proposal. Weekend is the only time I don’t feel exhausted. I start suspecting that there is something fundamentally broken in my relationship with work.

-

February 23

There is a seven hours difference between Kyiv and Montreal.

It was around 5am in Kyiv, still late evening in Montreal. I was sitting downstairs in my office, trying squeeze a few extra hours of work out of myself, before taking time off for spring break. That’s when I saw the news. I didn’t call anyone, not immediately, I didn’t move. I howled. That’s what I remember, howling and sobbing for a very long time.

I remember checking news every minute, then checking Facebook for personal updates, then texting, then waiting, then checking news, Facebook, texting, waiting, news… I remember Natashka hiding in the fields behind her house, I remember hearing nothing from Vika for ten long days and how I cried when she finally wrote back, I remember sitting in the hospital with my broken hand and getting updates from Olya who was trying to escape from Kyiv with her parents, I remember Natalya sending updates on her kids – her little Vira was only two at the time and so afraid of air raid alerts, I remember Olesya asking to pray for her parents in the occupied Irpin.

There is a seven hours difference between Kyiv and Montreal.

I woke up every day to the news of the fresh atrocities. I remember having a panic attack in the middle of the mall – I was supposed to meet some friends to talk about a difficult work situation. A few minutes later, I got the news of the bombing of Mariupol Drama Theatre. When it was evening in Montreal, the stream of news slowed down to a trickle. I remember laying down next to my son, who still slept in his baby cot, and praying, trying to say as many names as I could think of. Name by name by name by name.

I used to save the screenshots of news articles, photos, facebook posts about people killed by russia with their names and life stories, artwork that was even more heartbreaking than photos, and poetry. I have hundreds of those on my phone. Some of the artists and poets have since been killed in the war. 730 days is a very very long time. God have mercy on us.

-

February 21

In case you’re wondering what this photo is about – I was taking picture of the moon that is particularly bright tonight. This quaint little cemetery is right across the road from my son’s daycare. All French Canadian names. Generations of Brochus, Simards, Roches and Brunets. Where would the others be laid, I wonder. Anyway, it’s not scary at all, rather peaceful. Some local kids use it as a shortcut on their way to school. Poets are the most courageous people I know. I’m fine with writing poetry, as long as no one ever reads it. But I have friends who dare to read their poetry out loud – it makes me gasp every time, not only because it’s beautiful, but with a sheer force of their vulnerability.

I am reading Elena Kostyuchenko’s I love Russia. Kostyuchenko is an award-winning investigative journalist from Russia, a LGBT+ activist and a dissident. I saw her book at the library and thought “this is a really bad idea,” then I thought “I don’t have to love it, I don’t even have to care, but if I really want to believe in reconciliation, I have to at least try to listen.” See, what I learned is that reconciliation is always, always personal. Like any practice, it has to be holistic or it won’t mean anything at all. If I want to practice reconciliation, I cannot avoid of thinking about it in the context of Ukraine and Russia. This is still a very uncomfortable truth.

So, I started reading Kostyuchenko and haaving very conflicting feelings about it. I read the English translation – on the one hand it makes the whole experience surreal and alienating, seeing all familiar names in latin transcription, on the other hand it takes the edge off all the triggering material. I don’t think I would have managed to read it in Russian without breaking down. It also makes me understand why they keep supporting the war. In the hopeless, drunken and violent reality Kostyuchenko describes who would care about anyone’s life? Seriously, this book is not particularly trying to terrify and thus is thoroughly terrifying. At this point, I don’t feel sympathy for the people she describes, but I do feel some flicker of understanding.

I wanted to add the book to my “currently reading” list on Goodreads and got scared. What if my Ukrainian friends decide that I fraternize with the enemy? What if it triggers them? What if me reading the book will be interpreted as tacit approval of russian liberals? Again, through my own experience, I realize there is no common ground to stand on. And I don’t know where we can go from here.

-

Archeology of trauma 1

I was just watching another short documentary about the residential schools. There was a vivid description of a catechism class, where the nuns were describing purgatory to frighten children. This reminded me of a time, when someone in my protestant pentecostal church gave me a tape with a weird testimony of a person who supposedly went to hell (either in a dream or a vision or some kind near-death experience, I don’t remember). I remember that I really believed the authenticity of that tape (I must have been around 14) and the story about that person actually seeing what hell was like. I remember being terrified. When I think about it, I remember being terrified for most of my teens. Of course, there was my family situation, my dad being in a hospital and my mom, thin with worry, working 12-14 hours a day and chain-smoking in the kitchen the rest of the time. But the main source of my terror was the belief that the people I love will go to hell, unless I save them and convince them to join the church. I haven’t thought about it for a very long time, but tonight it dawned on me, what a terrible, traumatic burden was placed on me back then. I was a child, a teenager, I was lacking confidence and role models, I was lacking care, not because my parents were uncaring, but because they tried to survive in their own ways. And here I was tasked with saving everyone I knew, lest they burn in hell. Not scared for myself, scared for them. Here I was, frantically praying every night, unsure if God hears, always trying harder. Here I was, overcompensating for everything I believed was wrong with the world. I am still overcompensating. I can’t heal myself without healing that terrified 14-year old, who just listened to that terrible tape. I need to find words to reach her. I still want to save the world, save everyone I love, I just don’t think I want to carry the responsibility for it any longer.

-

February 19

It seems that we still have winters, if only for a little while. Monday, bathed in the glow of the winter sun and still retaining the flavour of the weekend, feels good and solid. All focus, zero adrenaline. Liberating myself from social media truly feels like liberation.

During my mid-day walk, I realized that I haven’t written down all the small moments of the weekend that I remember so lovingly:

Having a chance to cook and to clean on Saturday

Painting with kids with my favourite acrylic paints

Kids making guacamole together and eating it with chips

Watching a whole movie on Saturday night

Sunday morning crêpes

Kids’ friends coming over to play with them

First time sledging this winter

Finishing Emily Monnet’s Okinum

Sushi in the evening

Reading the poem written by a dear friend for my late cat Echo

Falling asleep on the couch, tired, but not exhausted

-

February 18

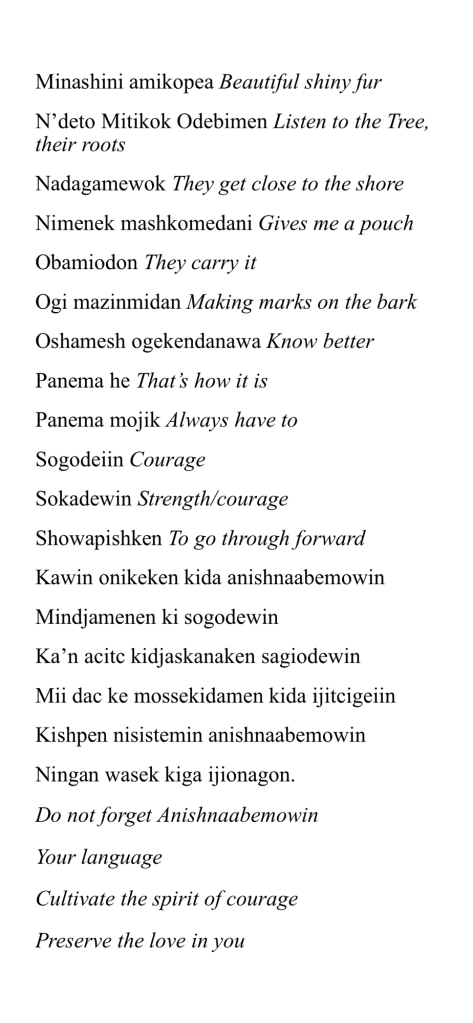

From Okinum by Emilie Monnet -

February 17

The unicorn I drew and my son coloured for his friend Emma’s birthday card. I named him Bob. Weekend is the most uncomplicated form of happinness. Just having a time on my hands that is not parcelled, not planned and not accounted for in Outlook. Cleaning, cooking, painting with children, watching an actual movie, not 15 minutes of an old sitcom, doing nothing, doing everything, not rushing towards something, rather, moving in circles. Ironically, I started the day tired and finish it rested. I have a feeling of having lived.

-

February 16

The snow is back. I was really happy to see it this morning, even though the wind was blowing it in my face. Tonight, when I was walking home, impatient to see my kids, the little snowbanks marking the border between the street and the front yards felt almost cozy. I don’t even like snow that much, I just like the comfort of having seasons and regular climate events.

I finished Kelly Barthhurst’s Crane Husband. It’s beautiful and very sad. Ever since I have children, I am disturbed by the stories revolving around siblings, especially when it’s sister and brother. I was holding my breath for most of the book, hoping nothing bad would happen to these fictional kids. This week, I’ve been listening to the podcast with Merlin Sheldrake and someone else, an artist, talking about fungi and challenging our ideas of individuality. We see ourselves as separate from the “outside world,” our skin serving as a barrier. What if instead we saw ourselves as a process, a constant exchange between the inside and the outside, our skin not as a barrier, but a porous membrane. I definitely feel my skin getting thinner, at least metaphorically. Everything gets to me. Almost everything.

The good thing about having thin skin is that kindness gets through even faster than all the bad stuff. The thing that made my day was that my husband decided to pick up kids early, because yesterday our daughter said that she had a bad day at school. This was pure kindness and it moved me in an unexpectedly deep way.

Everyone else will remember this day as the day that Alexey Navalny died. I honestly don’t know anymore how I feel about Navalny. I certainly don’t feel grief so many people seem to express. Nowadays, grief is reserved for the innocent. For me personally, Navalny is a product of the same colonial russian system that putin. He may be a better, lighter part of the system, but still a part of it. It is not putin that needs to disappear, but the whole system with its tyrants, oligarchs, it liberals and freethinkers, because as long as it exists, no one will be truly free. I don’t know if that will ever happen. Could colonialism be eternal? Anyway, let Navalny rest in peace.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.